Is Morality Improving?

Content

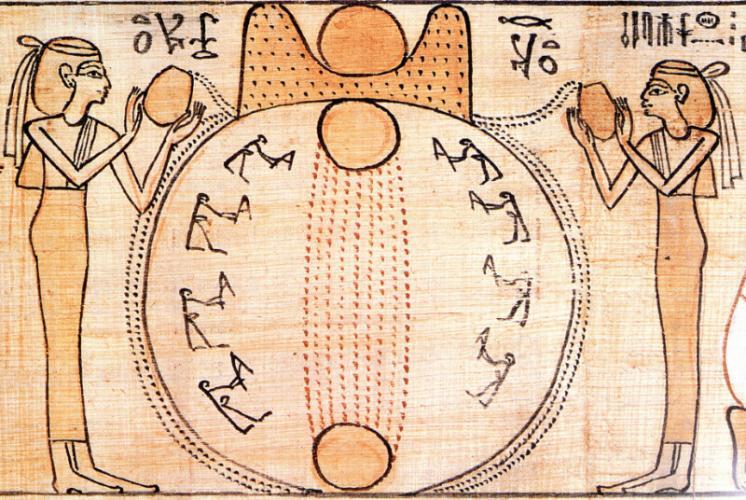

What clearly separates magic and superstition from more enlightened forms of spirituality is an evolving sense of morality. The religion of ancient Egypt was one of the first to extol advanced concepts of morality and ethics. In their belief, the source of this morality was the divine force of ma’at, which embraced truth, justice, order, and righteousness. This was a remarkable transformation for the time.

The Egyptians, instead of placing all emphasis on the auspicious control of unseen forces and magic, moved on to a deeper appreciation of moral values. Earlier religious practices were not overly concerned with whether individual actions were right or wrong; the main objective was to achieve a particular outcome, regardless of the means.

In the past, it was socially acceptable for religious devotees to curse others with evil or to pray for their demise. Notions of legitimate revenge were also common and often considered honorable. Such morbid convictions persist today, even among some who call themselves spiritual.

Human sacrifice was another common ritual in early societies. It was a socially acceptable way to appease the gods in order to improve crops or consecrate religious buildings. Indeed, it was not until the Iron Age (about 2,500 years ago) that human sacrifice was largely abandoned in the Middle East and other regions. But the practice persisted in other areas, such as the Americas, where it diminished only 500 years ago. This brutal practice later gave way to animal sacrifice, as indicated by archaeological and historical records.

We see this transition in the Old Testament, which is pervaded by notions of sacrifice, primarily as a means to remit sins, but also as a test of faith. One example is the Book of Genesis story in which God tests Abraham by asking him to kill his son, Isaac. Although Isaac was his second son, sacrificing firstborn sons was not uncommon in those times. But later, as a sense of morality grew, this primitive ritual was reformed by dedicating the firstborn son to the priesthood.

Even in the time of Jesus, the sacrifice of lambs and doves was considered necessary to atone for one’s misdeeds. And this fundamental notion of sacrificial atonement continued as a major theme in Christianity, as evinced by the atonement doctrine so ardently promulgated in the many letters of Apostle Paul—a lengthy collection of his thoughts and opinions that make up thirteen books of the New Testament.

This familiar, age-long belief that shedding blood was required for penance and salvation led to the early acceptance of Paul’s doctrine among budding Christians, most of whom were Jews or Greeks accustomed to the notion of sacrifice. These early followers viewed “sacrifice for atonement” as a reasonable explanation for the seemingly inexplicable death of their Master, the awaited messiah.

Today, however, blood sacrifice would not be considered moral, even if restricted to the sacrifice of animals. This change in attitude over time is just one indicator of the worldwide social trend toward a higher sense of morality.

For I desire mercy, not sacrifice; and the knowledge of God rather than burnt offerings.

– Hosea 6

God is not an irascible old man whose displeasure with the sins of mankind could be appeased only by the sacrifice of his perfect son, Jesus of Nazareth. And there is nothing in the New Testament to suggest that Jesus condoned any kind of morbid, blood sacrifice. Indeed, despite the barbarity of the time, he courageously delivered a cheerful and enlightened message—that his Father in heaven was a loving, merciful, and understanding God.

Jesus made it abundantly clear that a spiritual life and salvation (eternal life) are freely available to all who believe—to all who have simple faith in the compassion, goodness, wisdom, and grace of God—no sacrifice needed. Even Paul recognized this when he wrote, “It is the power of God that brings salvation to everyone who believes.”

Are You Right or Wrong?

Morality is a broad term, but in short, it refers to an individual’s innate sense of right and wrong behavior, whether alone or in a group. The goal of morality is to live a better life, not just for oneself but for everyone.

Morality should not be confused with government law or justice, even though the legal system is often guided by moral principles. It is society’s right and duty to pass laws and administer justice to control personal behavior, but this has little to do with an individual’s sense of morality. We can legislate social rules of behavior, but we cannot legislate an individual’s inner sense of morality.

Morality has nothing to do with so-called common sense unless, of course, one means good sense. But as the French philosopher, Voltaire, suggested long ago, good sense is not all that common. And common sense often has a strong cultural component, varying from person to person, society to society, and nation to nation. Without a doubt, morality should be reasonable, but it falters when subjected to social mores and the temperamental whims of individuals.

Morality is not religion, although it is the very foundation of religious experience because it opens the way for spiritual guidance and soul growth. This does not necessarily imply that all religious thought is moral. We cannot confuse religious doctrines and superstitious rules of behavior with a truly spirit-led morality. Instead, the spiritual quality of any religious belief or ritual is directly proportional to the degree of truth and morality it contains.

In the Buddhist tradition, morality is the foundation of the Noble Eightfold Path, a religious path one must walk as the prelude to liberation. Any progress along this path requires the practice and perfection of right speech, right conduct, right livelihood, and right effort. The very use of the word right explicitly defines the Eightfold Path as a moral mandate.

Set your heart on doing good. Do it over and over again and you will be filled with joy.

– Buddha

The Eightfold Path does not specifically outline which behaviors are right or wrong. This has some advantages because defining a long list of acceptable beliefs and behaviors often stifles true spiritual growth rather than setting it free to seek the spiritual guidance so necessary for a spontaneous life in the spirit. Indeed, allowing freedom of thought is one reason Buddhism has survived the test of time.

However, some followers of Western Buddhism take great pains to distance their religion from morality, insisting there is no such thing as right or wrong—that it is a false duality. Buddhist instructor Rodney Smith prefers to interpret right as meaning wise to avoid any connotation of morality, which he perceives as making judgments and passing laws (e.g., the Ten Commandments). But there is a significant difference between spiritual morality and society’s moral codes.

Even if we accept Smith’s use of the word wise, we are still left with the task of discriminating between what is wise and what is not because we are working on the premise that wise is good, but foolishness is not. In all our choices, we cannot escape the fact that we are trying to reach the best decision—the right decision.

At times, the best decision is not always clear. All moral discernment becomes a matter of recognizing relative right and wrong. At times, we need to consider many competing factors and then make the best choice in difficult circumstances. We can, however, improve our moral decisions by adhering to the highest values in life. And the highest values are always spiritual values.

See: Four Divine Values of a Spiritual Life

Morality and ethics define acceptable behaviors for the good of all members of society because, if society and civilization are to work at all, they require that we work together to solve common problems. Overall, the crux of morality lies in a sense of social duty and living a virtuous life.

Morality and ethics are firmly linked to notions of fairness. This applies to all levels of social interaction, including politics and economics. The most advanced (moral) political and economic systems are those that are fair to all members of society. They are ethical.

Morality is an outgrowth of reason but reaches a peak of discernment when guided by spiritual ideals. As one example of the potential cross-cultural nature of morals, consider the Golden Rule, which is to treat others as you would like to be treated—do for others as you would have them do for you.

Treat not others in ways that you yourself would find hurtful.

– Buddha

Your capacity to conduct a moral evaluation demonstrates your spiritual and supernatural nature—your superanimal ability to choose between truth and falsehood, good and bad, beauty and ugliness. In the spiritual domain, there is no evil, there is no falsehood, and there is no ugliness. By choosing goodness, truth, and beauty, you bring yourself into harmony with divinity and the wisdom of your Spirit Teacher. Consciously or not, those with discerning moral insight are invariably those who follow the Spirit Way.

Our moral thinking changes considerably when we realize and accept that we are all spiritual sons and daughters of a Supreme Being—a Creator God. This spiritual insight helps us to determine what is truly right and wrong in our relationships. It allows us to rise above the trivialities of life to see our personal problems in a different light.

An increasing sense of morality is essential to spiritual progress and God consciousness, but moral thought alone does not necessarily lead to more progressive levels of spiritual experience. If we wish to take morality to a more transcendent level, we need to enact our moral convictions in a positive, active, and spontaneous way—to actually live out the high morals we profess to believe.

The highest moral choice is the choice of the highest possible value, and always—in any sphere, in all of them—this is to choose to do the will of God.

– The Urantia Book

Making a Moral Evaluation

From a God-centered perspective, moral evaluation is the task of assessing all situations in light of divine values. Without a consciousness of spiritual values, a moral evaluation is no more than a matter of ethics, being largely conditioned by the social mores of the present.

A sense of morality cannot be learned from material science, social conventions, or religious doctrines. Instead, morality flourishes in a mind completely devoted to divine values and virtuous ideals, one free of preconceived notions, stubborn opinions, and inhibiting bigotries.

It’s easy to make excuses for our immoral choices. We can blame troublesome circumstances or some limitation of our character, or we can blame our parents, the government, economics, or even the environment. And if we are superstitious, we can blame it on misfortune, fate, or bad luck.

But to achieve any degree of spiritual maturity, we accept our present circumstances, take responsibility for our actions, and deal effectively with whatever situations arise, no matter how unfair they may seem. This is not to say we should never attempt to change the world or the circumstances of our lives, but instead that we learn, grow, and become wiser through our own moral efforts and experiences.

Morality is the essential pre-existent soil of personal God-consciousness.

– The Urantia Book

Deciding the right course of action is not always easy, and much depends on our experience, wisdom, sensitivity to divine values, and the depth of our connection with spiritual forces. But in all cases, it helps to think things through, meditate on immediate problems, and then to weigh all viable solutions.

Seven Vital Questions

Your values are important because they serve as your moral yardsticks for measuring and evaluating all situations and all decisions. Whenever you are in doubt as to the veracity of a moral decision, you can always ask yourself seven vital questions.

- Is it true? Are you being truthful with others and honest with yourself? Do you have ulterior motives that obscure the truth? Have you considered all the evidence?

- Is it good? Is your decision beneficial, productive, and positive? Have you considered all the consequences?

- Is it beautiful? Is it attractive, appealing, and charming? Is it graceful, elegant, and strong?

- Is it loving? Is it affectionate, friendly, and caring? Is it personable, kind, and respectful?

- Is it compassionate? Is it merciful, sympathetic, and comforting? Is it forgiving and tolerant?

- Is it fair? Is it just, impartial, and objective? Is it open-minded and virtuous?

- Is it helpful? Does it help or hinder others? Is it truly beneficial to your family, friends, and acquaintances? Is it for the greater good?